What is the CAC test and why should you care?

If you’ve been following a low-carb or ketogenic diet for a while, there’s a chance your cholesterol has gone up. And not just your HDL, but also your LDL—the so-called “bad cholesterol” (even though that’s a total misnomer). Maybe your cholesterol has actually gone sky-high, and your doctor not only wants you to start taking medication immediately but she’s also ordered you to quit your “crazy” high-fat diet. Even if you follow some other kind of diet—Paleo, vegetarian, low fat, or no special plan at all—maybe your cholesterol is high, and you’ve been told you need medication, or that you should exercise more.

Your doctor is only looking out for your best interest, but if they’re not up on the latest research, they might not know that your cholesterol level tells you very little about your risk for cardiovascular disease or a heart attack:

There’s “a growing volume of knowledge that challenges the validity of the cholesterol hypothesis and the utility of cholesterol as a surrogate end point.” (DuBroff, 2017)

It’s possible to have low cholesterol but massive heart disease, or to have very high cholesterol but be in great cardiovascular shape.

If you don’t want to start a war with your doctor, but you also don’t want to abandon a way of eating that’s helped you lose weight, have more energy, and maybe even reduce or eliminate diabetes medications, you can experiment with lowering your cholesterol by using the Feldman Protocol, which we featured here at Heads Up Health. But there’s a much better way to evaluate your cardiovascular health than just looking at cholesterol. It’s called the coronary artery calcium test (CAC). We’ll explore it in detail in a bit. First, let’s look a little closer at the problems with using cholesterol as an indicator of heart health.

Cholesterol is Protective

Evidence continues to build that cholesterol levels—including LDL—are not accurate indicators of cardiovascular disease risk and that the medical community as a whole may have gotten “the cholesterol story” very wrong. For starters, there’s the inconvenient truth that many people who have heart disease or experience a heart attack have “normal” or even low cholesterol. Low cholesterol is no guarantee against a heart attack, nor is high cholesterol a one-way ticket to heart disease and sudden death.

In fact, evidence suggests that higher cholesterol—again, including LDL—may actually be beneficial, especially in your golden years. A growing body of research indicates that high LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) is inversely associated with mortality in most people over sixty years of age. Inversely associated means, the higher the LDL, the lower the risk for mortality. To be fair, everyone’s risk for mortality is 100%, at least so far as we know. So when we say there’s a lower risk for mortality, it means that someone has a smaller chance of dying from anything other than a nice old age. This finding—that high LDL seems protective in some ways—has given researchers “reason to question the validity of the cholesterol hypothesis.”

This is especially true for older people. Epidemiological and observational studies show that, for most people over 60 years of age, high LDL-C is inversely associated with mortality. Researchers have also noted a “reverse epidemiology” among the elderly wherein slightly higher blood pressure, BMI, and cholesterol seem to be protective for health.

High Cholesterol Is Not a Disease

Cholesterol is a surrogate indicator. It’s a measurement, not an illness. Neither high total cholesterol nor high LDL-C, in particular, is a disease, in and of itself. They have long been considered markers for cardiovascular disease or risk of heart attack, but this ignores the crucial fact that neither the number of LDL particles in your blood nor the amount of cholesterol carried in them indicates anything about the degree of atherosclerotic plaque built up in your major arteries.

Measuring the amount of cholesterol in your blood provides no information whatsoever about the accumulation of calcified plaques in coronary arteries—that is, how “clogged” your arteries are—or are not. With this in mind, the obsessive focus on lowering cholesterol by any means necessary may have actually worsened the very epidemic of heart disease these treatments were intended to stop. The authors of one paper made a powerful case that “the epidemic of heart failure and atherosclerosis that plagues the modern world may paradoxically be aggravated by the pervasive use of statin drugs,” and proposed “that current statin treatment guidelines be critically reevaluated.”

Bottom line: statin drugs do lower cholesterol, but having lower cholesterol doesn’t guarantee protection against heart attack or heart disease. Plus, statins don’t just lower cholesterol. The biochemical mechanism by which they do so comes along with a host of other effects, some of which have drastic implications for cardiovascular health. To name just two, statins interfere with healthy mitochondrial function and also impair the synthesis of crucial vitamin K2. Vitamin K2 is a “traffic cop” for calcium: it helps deposit it where it belongs, like in your bones and teeth, and helps steer it away from places you don’t want it, like your artery walls, your joints, and your kidneys. So you can see how a deficiency in this critical vitamin could lead to arterial calcification, and it has nothing to do with the amount of cholesterol in your blood. (You can learn more about this fascinating but underappreciated vitamin in the book, Vitamin K2 and the Calcium Paradox.)

Enter the CAC Test

Since people who have heart disease or suffer heart attacks run the gamut from low cholesterol to high cholesterol and everything in between, using total cholesterol or even LDL as the determinant of whether someone’s at risk for a cardiovascular event is as misguided as gauging metabolic health and carbohydrate tolerance solely through measurements of blood glucose while ignoring the crucial role of insulin.

With all this in mind, more physicians are taking advantage of the coronary artery calcium scan. Unlike serum cholesterol measurements, which, again, are only surrogates, the CAC provides direct observation of arterial calcification that has already occurred. Not atherosclerosis an individual might or might not be at risk for based on their cholesterol, but the actual disease in progress. Why rely solely on surrogates when you can have a picture of the actual state of your arteries?

Data is accumulating that confirms what many doctors already know, even if they’re hesitant to admit it: cholesterol levels often don’t correlate with atherosclerosis. Data show that “significant ASCVD [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease] risk heterogeneity exists among those eligible for statins according to the new guidelines. The absence of CAC reclassifies approximately one-half of candidates as not eligible for statin therapy.” In plain English: half the people who would be put on statins based on cholesterol measurements were not candidates for these potentially dangerous drugs when their actual coronary artery calcification was measured.

Other studies bear similar findings. According to a study in Korean adults, over 50% of individuals for whom statin therapy was recommended had a CAC score of zero – no calcification. Based on actual arterial calcification—or, rather, the lack thereof—these individuals were at low risk for cardiovascular events, but without having gotten the CAC test, they might have been treated with statins based solely on the surrogate measurement of LDL.

What about the other side of this? What about people with normal or even “low” cholesterol? Does that go hand-in-hand with low risk for a cardiovascular event?

Not quite. Just as people with high cholesterol might have little to no arterial calcification, people with normal or low cholesterol could have high CAC scores and be at greater risk for heart disease, heart attack, or sudden death. This exact scenario played out in a study of CAC in low-risk women—low-risk, meaning they had cholesterol in the conventionally “normal” range: “Among women at low ASCVD risk, CAC was present in approximately one-third and was associated with an increased risk of ASCVD and modest improvement in prognostic accuracy compared with traditional risk factors.” Plain English translation again: one third of women assessed to be at low risk for atherosclerosis already had measurable arterial calcification. Say it with me for emphasis, folks: the amount of cholesterol in your bloodstream tells you nothing about the amount of atherosclerotic plaque in your arteries.

What is Coronary Artery Calcium and Why Test It?

Unlike your cholesterol, your CAC score gives you visual proof of arterial plaque. The reason to measure calcium, specifically, is, “Coronary artery calcification is part of the development of atherosclerosis; it occurs exclusively in atherosclerotic arteries and is absent in the normal vessel wall.” In other words, whether your cholesterol is low, high, or somewhere in the middle, if you have detectable coronary artery calcium, you have atherosclerosis.

And the reason to measure the extent of calcified plaque is that these plaques can rupture, break away from the artery wall, and block the artery, cutting off blood flow to the heart—which is one-way heart attacks happen.

If you’re wondering why calcium might end up in your arteries, the main reason is that it’s one of the ways your body repairs damaged blood vessels. According to Ivor Cummins and Jeffry Gerber, MD, in their book, Eat Rich, Live Long:

“The body’s response to damaged coronary arteries is always the same, and that response is what the CAC scan directly observes and quantifies. Your body tries to repair itself by depositing calcium in the damaged areas of the arterial wall. As the damage continues, these repair processes quicken. They desperately attempt to shore up the arterial walls before a rupture occurs. This growing calcium becomes the telltale sign of imminent danger—the ultimate canary in the coal mine.”

What is the CAC Test?

The CAC test, also called a “heart scan,” is a non-invasive, special x-ray of the heart and coronary arteries, performed via CT scan (computerized tomography). The scan itself takes only 20-30 seconds, but the whole procedure, from start to finish, takes about 10-15 minutes. Fasting is not required, but you may be asked to refrain from smoking or consuming caffeine for four hours before the scan since an elevated heart rate can reduce the image quality. Many insurance companies cover this test, but if yours doesn’t, or your doctor won’t order one for you, you can pay for it out of pocket, for about $150 in the U.S.

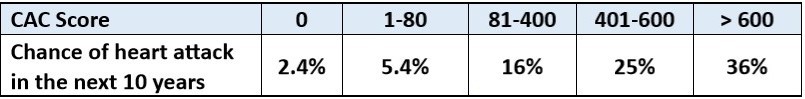

Test results are usually given as a number called an Agatston score. This number reflects a composite measurement of the total area of calcium deposits and the density of the calcium. According to the Mayo Clinic, a score of zero means no calcium is present, and the risk of heart attack is low. When calcium is present, the higher the score, the higher the risk for heart attack in the long term. A score of 100 to 300, considered “moderate plaque deposition,” is associated with a high risk of heart disease or heart attack over the next three to five years, and a score over 300 indicates very high to severe risk.

The key thing to know here is, many people (especially low-carbers) have very high cholesterol, but CAC scores of zero. Even if your score isn’t zero, if it’s very low, that might put your doctor’s fears to rest even if you have high cholesterol. Keeping the peace with your doctor isn’t a bad reason to have a CAC test, but an even better one is to put your own mind at ease.

The exact meaning of different coronary calcium scores differ depending on the source cited, but here’s a general guide, according to Axel Sigurdsson, MD:

Coronary calcium score 0: No identifiable plaque. Risk of coronary artery disease very low (<5%)

Coronary calcium score 1-10: Mild identifiable plaque. Risk of coronary artery disease low (<10%)

Coronary calcium score 11-100: Definite, at least mild atherosclerotic plaque. Mild or minimal coronary narrowings are likely.

Coronary calcium score 101-400: Definite, at least moderate atherosclerotic plaque. Mild coronary artery disease highly likely. Significant narrowings possible

Coronary calcium score > 400: Extensive atherosclerotic plaque. High likelihood of at least one significant coronary narrowing.

Here’s another look at CAC scores, from Eat Rich, Live Long:

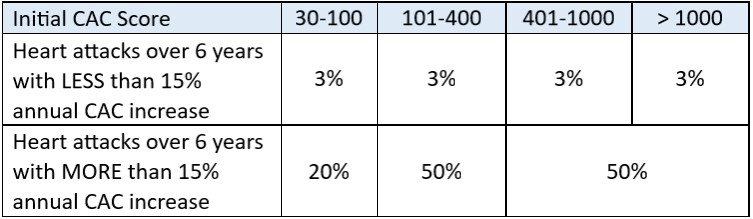

However, a high CAC score doesn’t mean you’re automatically in imminent danger. If your plaques are stable—that is, they don’t keep increasing over time—your risk for a cardiovascular event remains pretty low. On the other hand, even if you start out with a relatively low score, if that score increases substantially over time, your risk is much higher. Remember, as arterial damage worsens, calcium deposition increases, so if your CAC score is going up, your arteries are in worse shape.

From Eat Rich, Live Long:

Not a Perfect Test

Although a low CAC score generally indicates a low risk for cardiovascular events or disease, it’s not a full guarantee. Unstable coronary plaques vulnerable to rupture may be present in the absence of calcium deposition. And a high CAC score increases the chances that you have vulnerable plaques, but it doesn’t identify specific places where a rupture or blockage might occur. Dr. Sigurdsson wrote:

“The presence and extent of coronary calcium are first and foremost markers of the extent of atherosclerosis within the coronary arteries. Nonetheless, it is important to understand that the coronary calcium score does not necessarily reflect the severity of narrowing (the degree of stenosis). Still, a patient with a high calcium score is more likely to have a significant narrowing of a coronary artery than a patient with a low calcium score. An individual without coronary artery calcification is very unlikely to have a severe narrowing of a coronary artery. Although cardiovascular events can occur in patients with very low calcium scores, the incidence is very low.”

Take Action

If your CAC score is zero or very low, keep doing what you’re doing! But if you have a high score, don’t let fear overtake you. Instead, use that knowledge to spur you to action. Specifically, consider adopting a low-carb, higher-fat diet. Nothing’s more damaging to your blood vessels than chronically high blood sugar or insulin. Low carb and ketogenic diets have been shown time and again to reduce inflammation, reverse metabolic syndrome, and be beneficial for cardiovascular health.

Not only can you slow the progression of arterial calcification, but you can actually reverse it. This was virtually unheard of in the past, but that’s because the only things recommended to people with high CAC scores was a low-fat diet and cholesterol-lowering medications. Since coronary artery calcium has virtually nothing to do with your cholesterol and a lot more to do with repairing damage to blood vessels injured by chronically high glucose and insulin, it’s no wonder a high-carb diet and cholesterol medications made no impact.

On the other hand, a ketogenic or low-carb, high-fat diet might be just the thing to help those blood vessels heal and restore your cardiovascular system to its best functioning. Use the tracking system here at Heads Up Health to record your CAC score and keep track of all your other health data in one convenient place.

[maxbutton id=”7″ ]

Are there published double blind papers demonstrating that LCHF diets actually reduce CAC scores?

And if there are would you cite them or send an email link ?

Thank You

Even if my humble opinion this is not the best of the studies, it is the first to look at the calcium score related to low carb consumption:

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-of-nutrition/article/lowcarbohydrate-diets-and-prevalence-incidence-and-progression-of-coronary-artery-calcium-in-the-multiethnic-study-of-atherosclerosis-mesa/70E006AD304D0EA065A0509B1EA5BFAF